Kartograf som 1875 tog fram en tematisk karta där han jämförde befolkningen i Europa.

ZAHRTMANN, CHRISTIAN CHRISTOPHER.

1793-1853. Född i Viborg, död i Köpenhamn.

Dansk sjöofficer. Som ung kadett och löjtnant utmärkte han sig under kriget med England 1807-14. Han avancerade senare och blev så småningom viceamiral 1852. Då kriget med England var slut påbörjade Zahrtmann studier i hydrografi och geodesi, och blev 1819 anställd vid mätningar på Jylland. 1826 blev han direktör för Sjökortsarkivet. Där gjorde han ett förtjänstfullt arbete vid utmätningen av de danska farvattnen och anläggningen av en rad fyrar. 1848-50 var han marinminister och 1852 blev han överekipagemästare vid Holmen i Köpenhamn. Han offentliggjorde ett antal avhandlingar om kartografiska och sjömilitära frågor.

Bricka.

1803-80.

Tysk förlagsbokhandlare. Född i Siblingen, död i Leipzig. Efter utbildning i bokhandlarkonsten i Basel, Genève, Paris och Freiburg etablerade han sig i Leipzig 1833. Han intresserade sig speciellt för illustrerade verk och gav bl.a. ut 'Pfenningmagazin' och 'Illustrierte Zeitung'. Förlaget existerade åtminstone till 1950-talet.

Bland arbeten.

Pfenningmagazin.

Illustrierte Zeitung.

Der Grosse Brockhaus.

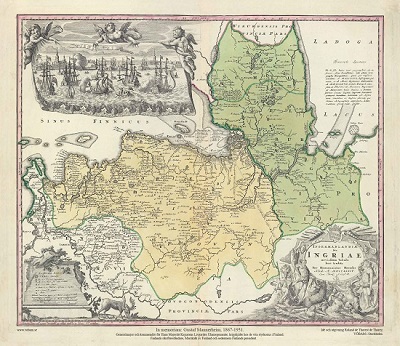

Ingermanlandiae – Homanns Erben 1734

Dräktbild - Vingåkers socken.

Olaus Magnus text till den berömda kartan "Carta Marina".

Texten finns även på katalanska, spanska och engelska.

Bureus karta över norden

Kartor och atlaser

Bilder och planschverk

Teckenförklaringar

"The Mapping of Mars."

by Peter J. K. Louwman.

Amateur astronomer, Louwman Collection of Historic Telescopes, Wassenaar, The Netherlands.

The most familiar type of globe is the terrestrial one. Also familiar, but less common is the celestial. For a true globe collector it is most desirable, of course, to own a pair of these globes, identical in size, by the same maker. For me, as an enthusiastic amateur astronomer, two even rarer types of globe have always attracted me: globes of the Moon and of Mars. Technically, these globes share many details with the terrestrial globe, but they offer some curious differences worth looking at.

A Moon globe that was published before the time of the “Space Age”, for instance, shows us surface details as seen with the help of a telescope, of only one half of the Moon. The other half was blank, because no surface details could be observed. This is due to the fact that the Moon, during its revolution around the Earth in one month, always presents the same side of its surface towards the Earth.

When the first spacecrafts made the voyages to, and later travelled around the Moon, the features of the hidden side could be charted. The first pictures of that part of the surface were successfully made by the Russian “Luna 3” in October 1959. This led to the production of Moon globes with all details of the entire surface by publishers in the U.S.A., Russia and elsewhere. Ever since the discovery of the telescope, the surface of the planet Mars has been observed intensively. At first, only crude sketches of surface detail were all that could be achieved. Later on, with better telescopes and observing techniques, more and more details could be charted.

Unlike the Moon, Mars rotated in about 24 ½ hours and thus gradually presents its entire surface towards the Earth. Observations made at intervals enables astronomers to compile maps of the whole surface. Consequently, it was possible to convert the surface details of the two-dimensional maps onto the three-dimensional surface of a sphere to create a Mars globe.

A further important difference between the Moon and Mars is that where the surface characteristics of the Moon are permanent, those of Mars change with time. The reason for this difference lies in the fact that Mars has an atmosphere and the Moon does not. Winds and dust storms on Mars constantly change the appearance of certain parts of its surface. Well-known temporary changes occur at the with-capped North and South poles, which change dramatically in size during the cycle of seasons of approximately 687 days. The polar caps consist of water ice and carbon dioxide. In the summer season of the northern hemisphere for instance, the cap on the North Pole shrinks to a very small area, while that of the South Pole increases. These changes are due to the evaporation and sublimation of carbon dioxide in particular. On modern Mars globes the polar caps are illustrated at their minimum size so that no surface features are hidden under the caps.

To modern astronomers , familiar only with the beautifully illustrated Mars maps compiled from the information gathered by Mars space missions, it might come as an unexpected, perhaps even annoying, surprise that old maps and globes show the North Pole at the bottom and the South Pole at the top. The explanation for this representation lies in the fact that astronomical telescopes give an inverted image: “up” and “down” are viewed as “down” and “up”.

As a matter of fact all old astronomical books, maps and journal publication (until around 1960, but in some cases after that year also) always illustrate pictures of heavenly bodies upside-down. This is also the case with drawings, maps and photographs of stellar objects like stars and nebulae. Why bother to turn it around, astronomers reason, when the inverted image is the way one actually sees and observes it through a telescope?

To me, a Mars globe with the traditional astronomical orientation is very appealing. Recently, I was lucky enough to acquire one; this globe is a product of a tremendously interesting period in Mars research and I was very glad to add it to my private collection of astronomical objects of historical significance and cultural importance.

This Mars globe was made by Ingeborg Brun of Norway in about 1920. For the making of it, she used information that is entirely based on the work of the famous American astronomer Percival Lowell. Lowell built his observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona in 1895 and devoted much of his time and money to observing Mars and doing research on its canals, which were at that time very popular with the general public.

Unfortunately, Lowell’s world-famous observations of the canals and of the supposedly seasonal growth of vegetation along them eventually proved to be caused by optical illusions. On modern pictures obtained by space probes, nothing resembling “canals” has ever been found, nor any clues to water on the planet’s surface. Nor have the Mars landers found any additional clues.

Nevertheless, the research of Lowell and others, undertaken some 100 years ago now, belongs to a short but very fascinating period in astronomical research.

Gazing at my wonderfully detailed and exquisite Lowell Mars glob continues to impress me and helps me to understand this fascinating period of astronomy and globe it produced.

Christie’s, London. Fine Globes and Planetaria, Tuesday 5 November 2002.